-

Ethnology of the Greenland Eskimos

Encyclopedia Arctica 8: Anthropology and Archeology

Ethnology of the Greenland Eskimos

001 | Vol_VIII-0078

EA-Anthropology

(Therkel Mathiassen)

ETHNOLOGY OF THE GREENLAND ESKIMOS

Introduction

Greenland has a population of about 21,000. Of these only a few

hundreds are Danes, while the rest are Greenlanders, a mixed population,

formed during the modern period of more than two hundred years that

Greenland has been under Danish government, mostly through intermarriage

between the originally pure Eskimo population and Danes. The Eskimo blood,

however, dominates, and the children of these mixed marriages nearly always

speak the Greenland (Eskimo) language. In certain districts there are a

good many pure EskimosThe population of Greenland falls naturally into three groups: The

Polar Eskimos number about 300 and live in northwestern Greenland north of

Melville Bay, in the Thule or Cape York district. The West Greenlanders,

numbering about 19,000, inhabit the west coast from Melville Bay in the north

to Cape Farewell in the south. The East Greenlanders, about 1,300, are on the

east coast, chiefly in the Angmagssalik district, with small groups at Scoresby

Sound and Skjoldungen. (The Scoresby and Skjoldungen groups are recent immi–

grants brought by the Danes, chiefly from Angmagssalik but a few from the

west coast.) Each of these three main groups has a stamp of its own, indicating

a rather long separation.

002 | Vol_VIII-0079

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

The Polar Eskimos

The Polar Eskimos inhabit the territory between Melville Bay and

Smith Sound; but on their hunting excursions they often go far down into

Melville Bay, north to Inglefield Land, and, earlier, west to Ellesmere

Island. As the whole population numbers only about 300, it can be seen

that their country is very thinly populated. The main settlement is the

trading post Thule in Wolstenholme Sound: there are, besides, two small

outposts, Siorapaluk in Inglefield Bay and Savigssivik near Cape York, as

well as a changing number of small villages, not all of which are inhabited

every year.The Polar Eskimos were discovered in 1818 by John Ross; but the knowledge

of them is mostly due to two men: Peary, who used their country as a base for

his North Pole expeditions from 1891 to 1909, and Knud Rasmussen, who together

with Mylius-Erichsen and Harald Moltke spend the winter 1903-04 there, and

who in 1910 erected there the Thule station as a base for his "Thule-Expedi–

tions" and at the same time as a trading pos [ ?]t , which could partly finance

his expeditions. After the death of Knud Rasmussen, the Danish Government

took possession of the station.The Polar Eskimos are still nearly pure Eskimos; there is, however, a

little intermixture of white and West Greenland blood, and these half-breeds

are usually more prolific than the pure Eskimos, whose marriages often are

childless. A proper study of the physical anthropology of the Polar Eskimos

has never been made. In most features they resemble the other Greenlanders

(see later, under the West Greenlanders). According to the few measurements

that have been taken they seem to be rather small, the men with heights from

003 | Vol_VIII-0080

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

163 to 152 cm., the women from 150 to 142 cm. A considerable number of them

have "Indian" noses.Mention should be made of the highly arctic conditions under which the

Polar Eskimos, the northernmost population in the World, live. Their terri–

tory is large, but nearly all the land is covered by the inland ice; it is

from the sea that they have to take their food, and this is frozen over for

ten months of the year. The climate is also high arctic, with a winter dark–

ness of three or four months and a similar period of midnight sun in the

summer; the summer is short and cool, and the winter is long with an average

temperature of about 30 to 40° Centigrade. In spite of these severe natural

conditions, this little group had for centuries been able to live in comfort

at this remote and isolated place.In the short period of open water the Polar Eskimos hunt walrus, narwhal,

white whale, bearded seal, and fjore seal from kayaks. Formerly some caribou

were hunted, but they are now nearly exterminated, and musk ox hunting on

Ellesmere Island has been prohibited by the Canadian Government. Some salmon

are caught in lakes and rivers. Birds form an important food item, especially

the little auks, which breed in millions on the cliffs; egg collecting is

also of some importance. The birds are caught with bag nets on long poles

and are put up for winter consumption in whole seal s kins, the fat of which

penetrates the birds. This bird catching was formerly much more important

than now, being nearly their only summer occupation.Such important culture elements as the kayak, the bow, and the salmon

spear were unknown in the country until they were introduced by a small group

of Baffin Islanders, immigrating in the 1860's. Archaeological investigations

show, however, that these elements had been known earlier in the district;

004 | Vol_VIII-0081

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

but there was evidently a period of several hundred years when they were

unknown, probably on account of lack of wood, which is very sparse in the

district. The kayak and kayak implements are of the same clumsy types as

used in Baffin Island, and the Polar Eskimos are not nearly as clever kayak

hunters as the other Greenlanders.By the latter part of September the new ice begins to form in fjords

and bays. In the fall seals are caught at the breathing holes on the smooth

ice, and walrus are caught from the ice edge and when they push their heads

through the new ice to breathe. In the darkness of full winter, hunting is

nearly impossible, but foxes can be trapped; in this period it is necessary

to depend on the caches of meat, mostly seal and walrus, laid up during the

spring hunting.In the late winter or early spring, when the sun has come back, the

walrus hunt from the i d c e edge begins again, and this is also the time of the

bear hunts, the favorite occupation of the Polar Eskimos. In spring and early

summer the basking seals are caught on the ice ( utoq utoq hunting), previously by

harpoon, now always by rifle and shooting-screen.Now that the caribou is nearly exterminated, the only land animals hunted

are the arctic hare and the fox. The hare is important because its fur is

used for stockings; the fox, earlier caught in stone traps but now always in

steel traps, is now the base for the economy of the whole district. For with

the foxskins the Polar Eskimo can buy at the trading pos e t s the products of

civilization to which they are now accustomed: rifles, ammunition, tools and

ironware, wood, textiles, tobacco, and some kinds of white man's food.The winter houses are small, rounded, half underground, rather narrow

at the back, wider in the front part, where the narrow, sunken doorway begins.

005 | Vol_VIII-0082

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

The building material is mostly stones, flat slabs which are abundant

in the district. The domed roof is also usually built of stones, arranged

on the catilever principle; sometimes whale bones are used in the construc–

tion; wood is seldom used. The back part of the house is occupied by the

raised platform, also built of flat stones; at the ends of the patform are the

lamp places; over the soapstone lamps are the cooking pots, hanging down

from the roof on thongs; here the cooking is done and here the women have

their working places. On winter journeys snowhouses are built, and there

are also used as temporary dwellings at the hunting places. The sonwhouses

of the Polar Eskimos are smaller and more poorly built than those of the

Central Eskimos, which are in use throughout the whole winter. The summer

dwelling is the sealskin tent, consisting of a vertical square frame of

wooden poles, against which rests a number of slanting poles, the whole

covered with sealskin. The old winter houses are now being replaced by

wood and sod houses of the West Greenland type; most of the well-to-do

families also have canvas tents.The most important means of communication is the dog sledge. It is

[ ?] rather long and narrow, with uprights; now always made of

wood, the earlier sledges were of numerous pieces of bond and wood lashed

together. A team usually consists of about ten dogs, hitched to the sledge

fanwise, with all the traces about the same length. The Polar Eskimos are

usually very good dog drivers. Because of the considerable amount of meat

procured by the walrus hunt, they can keep many dogs and feed them well;

the teams are always tied up and are not allowed to mix. The women's boat

seems never to have been used by the Polar Eskimos. The scarcity of wood

has made it difficult to construct these boats and the short period of open

006 | Vol_VIII-0083

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

water has made them less necessary than elsewhere; the dog sledge, on

the other hand, can be used ten months of the year.The clothing of the Polar Eskimos is rather peculiar. Their old

dress consisted of a shirt of birdskin with the feather side inside; over

that a hooded coat of foxskin, which in spring and summer [ ?] was replaced

by a sealskin coat. The men wore bearskin trousers and boots of white, hair–

less sealskin with hareskin stockings; the women wore quite short foxskin

trousers and very long white sealskin boots. Urine tanning of skins is not

used.The implement culture of the Polar Eskimos differs in many respects

from that of the other Greenlanders. This is to some extent due to the

influence of the immigrating Baffin Islanders. The clumsy kayak, the harpoon

without a throwing board, the big hunting float made of a whole sealskin, the

drag float for the harpoon line, the three-pronged salmon spear, were all

introduced by the newcomers. In other cases we find primitive features such

as harpoon heads of Thule type with open-shaft socket and the winged needle–

case, still used until about 1900. These elements are no doubt reminiscences

of the Old Thule culture, which previously existed in this region, and

certain features in the clothing, such as the bearskin trousers and the long

women's boots, which they have in common with the now extinct Sadlermiut

of Southampton Island, probably have the same origin.The spiritual culture of the Polar Eskimos has been given especial

study by Knud Rasmussen, who has published extensively on the subject.

Erik Holtved, who spent three years among them (1935-37 and 1946-47) has

also collected a great deal of material, as yet unpublished. All the Polar

Eskimos are now baptized.

007 | Vol_VIII-0084

EA-Anthrop. Mathiasson: Greenland Eskimos

The West Greenlanders

The West Greenlanders numbering about 19,000, are far the most numerous of the three groups

of Greenlanders. They inhabit the more than 1,100-mile coast line between

Devil's Thumb, just south of Melville Bay, and Cape Farewell, a coast much

cut up by large fjords and fronted in many places by a belt of skerries.

In most places there is a wide stretch of ice-free land between the coast

and the inland ice, but this land is mostly mountainous, often with local

glaciers. In other places the coastal land is rather narrow, and the in–

land ice sends large glaciers out into the sea, producing icebergs; that

is the case in Disko Bay, Umanak Fjord, and the Upernivik region. Because

of the great distance from north to south the climate varies considerably.

In the north we have a high arctic climate with cold, dark winters, and

with the sea frozen over the entire winter; in the south the climate is

more subarctic, with no winter darkness, with cool summers and stormy, not

very cold winters, and without a regular ice-covering of the sea.The West Greenlanders since 1721 have been under the Danish Government,

and have, as a result, been greatly influenced, both physically and culturally.

The population is racially rather mixed, mostly through intermarriages between

lower Danish functionaries and Greenland woman. This half-breed population

seems to be prolific and vigorous, and their number is rapidly increasing;

nearly all of the leading Greenland families now have half-breeds. Only in

the far north, in Upernivik District, and in the southern part of Julianehaab

District, where a good many East Greenlanders have settled, are there larger

populations of pure Eskimo origin.The West Greenlanders now inhabit a number of settlements, each with a

large trading station, and usually also a church, school, hospital, and often

008 | Vol_VIII-0085

EA-Anthrop. Mathiasson: Greenland Eskimos

a wireless station. The center of administration is Godthaab; other large

places are Julianehaab, Sukkertoppen, Egedesminde and Jakobshavn. Each of

these places has from 600 to 800 inhabitants. Other settlements are

Frederikshaab, Holsteinsborg, Godhavn, Christianshaab, Umanak, and Upernivik;

The mining towns Ivigtut (cryolite) and Qutdligssat (coal); about 50 small

trading posts, usually also with a church and school, and about 120 smaller

settlements. Julianehaab District is the most densely populated region.

West Greenland is divided into two parts, each with its Governor: North

Greenland with its center is Godhavn, comprising the districts of Upernivik,

Umanak, Jakobshavn, Christianshaab, Godhavn, and Egedesminde; and South

Greenland, comprising Holsteinborg, Sukkertoppen, Godthaab, Frederikshaab,

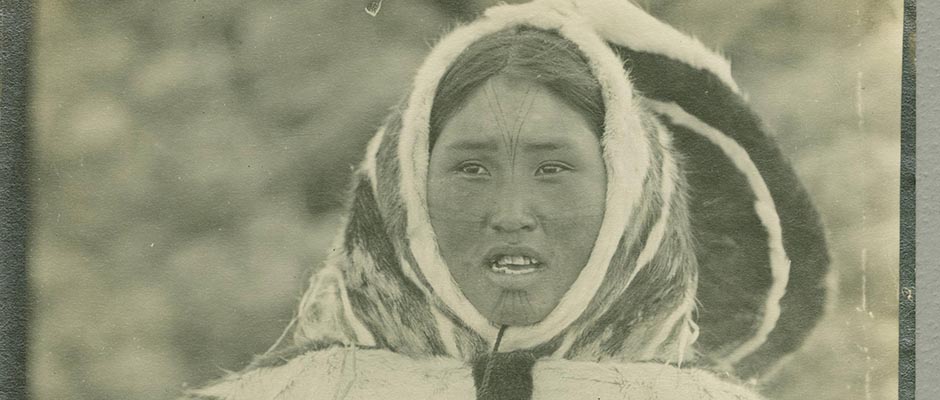

and Julianehaab.The stature of the West Greenlanders is usually between 160 and 165 cm.

for the men, about 150 to 155 cm. for the women. On the average they are

powerfully built and plump; the length of the trunk is comparatively large;

the chest is broad and powerful; the legs are rather short, the hands and

feet small. The shape of the skull is dolichodephalic, with an index usually

between 70.5 and 72; it is characteristically roof- or crest-shaped. The

brain capacity is large, about 1,400 to 1,500 cm. On the skull the face

breadth is not very great; but because of the frequently big cheeks the

faces of the living Greenlanders look very broad and flat, with noses that

protrude little; this with the often "oblique" eyes give them a mongolloid

aspect. The hair is black, rather coarse and lank, and abundant; there is

usually not much beard. The eyes are dark brown, the complexion yellow brown

or light olive.What is said here about the physical characteristics of the West Greenlanders

009 | Vol_VIII-0086

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

refers to those of pure or nearly pure Eskimo origin; for the most part

it also applies to the East Greenlanders and to the Polar Eskimos.The old culture of the West Greenlanders is known through reports

from the time of first colonization, most from Hans Egede and his mission–

ary successors, his son Poul Egede and his son-in-law Glahn; also the

missionaries Cranz and Fabricius, and Dr. H. Rink, who was director for

the government of Greenland in the middle of the 19th century. In later

years Birket-Smith made a thorough study of their material culture, Thal–

bitzer studied their spiritual culture, and Knud Rasmussen collected a

considerable number of old tales.The following description of the material culture of the West Green–

landers treats of conditions before the modern development which the

great fisheries have brought in the 20th century.The annual hunting cycle differs a good deal in different parts of

the country. Both in North and South Greenland seal hunting is the main

occupation. In North Greenland the sea ice breaks in June, and then the

big seals, the bladdernose and saddleback, are hunted from Kayaks, sometimes

also the fjord seal and white whale. Halibut and shark and large numbers of

the small capelins ( angmagssat ) are also caught. At certain places there is

in the late summer and early fall some caribou hunting; eiderducks, auks, and

other sea birds are caught throughout the summer, especially on the cliffs

where they nest in millions; there many eggs are also collected. Salmon

are caught in the rivers, now mostly by netting. In October-November, when

the sea ice has formed, seals are caught [ ?] from the ice; in olden times this

was done mostly at the breathing holes, now it is mostly with nets fastened

under the ice. When the ice is too thick for net-hunting, halibut and shark are

010 | Vol_VIII-0087

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

caught with hooks through the ice. In the winter foxes are trapped. In

the spring fjord seals are hunted while basking on the ice, and narwhal

and white whale are also hunted from the ice edge or through holes and

openings in the ice.In South Greenland no regular sea ice is formed, and kayak hunting

can be carried on the whole year. On the other hand, in the farthest south,

especially in the Julianehaab District, there is much drift ice in summer;

this comes from the east coast around Cape Farewell, and following the ice

are many seals, mostly bladdernose and bearded seal, which from the basis

for the summer hunt here. At this time a large part of the population

moves from winter settlements to the camping places closer to the o ep pe n sea

and the drift ice, where the hunting is performed. In the northern part of

South Greenland the capelin catch in June plays an important role; saddle–

back seals are also hunted from kayaks. In July and August many families

move into the fjords for caribou hunting and salmon fishing. In September

the families return to their winter settlements, living on saddleback seal,

hunted from kayaks, and some salmon. In October hunting of sea birds,

especially eider ducks, is of some importance in many places. This seal–

and bird-hunting from kayaks continues throughout the winter, often under

difficult condition, in [ ?] stormy weather and rough seas. In spring there

is in the North some hunting of basking seals, while in the South the

bladdernose hunting begins in April. In m M ay the removal to the tenting

places begins.It is not difficult to understand that it is on the kayak and the

kayak implements that the West Greenlanders concentrate their skill and

craftsmanship. The kayak is slender and elegant; its shape varies slightly

011 | Vol_VIII-0088

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

from district to district, with stems somewhat upturned here and there,

according to its use in more or less rough seas. Around the rim of the

hole the kayak frock can be lashed watertight, so man and m k ayak are one

and can turn over without the man being soaked. Every good kayak hunter

is able to turn over with his kayak by using his paddle in such a way that

a capsizing will not be catastrophic. The kayak rack, on wh ci ic h the harpoon

line lies rolled up, is raised above the deck, so the line does not become

tangled if the waves wash over the deck. To the right of the hole the

harpoon is placed; it is hurled with the throwing board, another clever

invention. The kayak harpoon has a movable foreshaft and a loose head,

fastened to the line which in turn is fastened to the f l oat, an inflated

sealskin which rests on the afterdeck and is kept in place by two curved

pieces of wood fastened under one of the many seal thongs that run from

side to side on the kayak deck. The shape of the harpoon head varies a

good deal, each hunter having his favorite type; all of them are flat, with

one or two basal spurs, with or without barbs on the sides. Other kayak

implements that are placed on the kayak deck are the lance, bird dart, and

throwing boards. [ ?]

The lance has a movable foreshaft, but a fixed blade, and is often used with

a throwing board; its function is to kill the wounded seal. The bird dart,

with its throwing board, has a fixed point and three barbed side prongs to

catch the bird, if the end point misses. To the cross-thongs on the deck

are also attached a long, usually two-edged hunting knife, towing implements,

consisting of lines with toggles to hold the dead seal to the kayak, and

some wound plugs — wooden pieces to close the wound and prevent the blood

from running out. Today, the kayak outfit always includes a rifle, placed

012 | Vol_VIII-0089

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

in a sealskin bag, and a shooting-screen of white linen cloth, which gives

the kayak the appearance of a small ice floe.For caribou hunting bows of wood and baleen with sinew backing were

formerly used; now rifles are always used, and only during a few months are

caribou allowed to be killed.Capelins are taken with big scoops. Most salmon are now caught with

nets, formerly made of baleen strips. Salmon leisters are still used.During recent years a radical change in the hunting conditions and the

mode of living have taken place, mostly in South Greenland. The reason is

partly climatic change, which has raised the temperature of the sea water,

thus causing an enormous increase in the number of fish, especially cod, while

at the same time the seals in this area have become more scarce; reason for this is the promiscu–

ous seal-hunting on the ice along the East Coast of Greenland by some European,

mostly Norwegian, hunting expeditions. It has, then, become necessary to change

from seal hunting to fishing in the whole of South Greenland and also in some

of the southern parts of North Greenland. The cod fishing is mostly done by

jigging from small boats and kayaks, but some fishing is done from motorboats

that are large enough so that halibut and other fish can also be taken. This

has caused a concentration of the population at the larger settlements, where

the fish can be sold and treated.Another activity which in recent years has been of importance in South

Greenland, is raising sheep, and most of the place d s suited for that purpose

have now been occupied by sheep breeders, who often are well-to-do compared

with the fishermen. At Igaliko, the Norsemen's old bishop's seat, a group

of cattle breeders has settled down. In addition, and increasing number of the

population are in the service of the Government as teachers, outpost managers

013 | Vol_VIII-0090

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

and other officials, and as craftsmen, sailors, or workers. At the Qutligssat

coal mine large numbers of Greenlanders are engaged as miners, while the

Ivigtut cryolite mine is worked by Danish laborers. Because of these changes,

the old hunting technique in large parts of the country is now rapidly dis–

appearing. In North Greenland, however, especially in its northern part,

sea hunting is still the main occupation.The old type of winter house, used during the eighteenth and part of

the nineteenth centuries, was the large rectangular common house, usually

built on doping terrain, so that the back part had to be dug a little into

the ground. The length used to be between 6 and 10 meters, according to the

number of families, the width about 5 meters. The walls were built of stones

and sod; the roof was flat, constructed of wooden planks, covered by skin and

sod. The entrance was through a long, narrow passageway, sunk deeper than the

floor and at right angles to the house. The front of the house had a number

of windows with gut-skin panes. The back part of the house was occupied

by a raised wooden platform; the floor was covered with flat s t ones, along

the sides and the front of the house were smaller platforms [ ?] for unmarried

people and guests. The main platform was divided by skin curtains into as

many rooms as there were families in the house up to about ten. In front of

each platform-division there was a lamp table for the soapstone lamp, the

cooking pot, and other househol e d utensils; above the lamp was the drying rack.

Below the platform stood the urine container, a big wooden bowl in which skins

were soaked before being prepared for clothing. The roof was supported by a

number of strong, vertical poles, one at each platform-division. This type

of house has now gone out of use in West Greenland, but is still used in

Angmagssalik. At remote places it may still be possible to find houses of a

014 | Vol_VIII-0091

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

similar construction, but smaller for only one or two families.Another house type still in use is not sunk into the ground, has walls

of stones and sod, sometimes a wooden panel, and usually a wooden floor.

These houses have larger windows with glass panes, an iron stove, a flat

roof, and a little entry room. This is the type of house ordinarily used

by the poorer West Greenland population, especially in the farthest north

and south. At other places these dwellings have been more and more displaced

by wooden houses with thatched roofs. It is mostly the larger incomes, de–

rived from fishing which have enabled the Greenlanders to build these wooden

houses, but such houses, especially if badly built, require more heating and

are not as warm as were the old houses.In the spring, mostly in May, the whole population formerly moved into

tents, and the roof was taken off the old winter houses. The tents had a

wooden frame and a covering of sealskin; they had a little raised platform,

covered with skins. Now the skin tents in most placed have been displaced

by canvas tents, and most of the fishing population do not move out of their

winter houses at all; a condition not good for their health.The soapstone blubber lamp, the old, most important household utensil,

is not used much any more. It is a big, half-moon-shaped bowl, placed upon

a lamp stand of wood, with a hollow to receive the dripping blubber. Now

train oil or kerosene lamps are used.The old means of communications were the dog sledge and the umiak, the

women's boat. The dog sledge is used from Holsteinborg to the North and is

still the only means of communication in winter. The sledge is rather short

and wide, with high uprights. The dogs are attached fanwise and the traces

are of the same length. The dogs are not tethered when at the settlement,

015 | Vol_VIII-0092

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

and sledges, kayaks, skins, and meat have to be placed on wooden scaffolds

out of their reach.The umiak, the 9 to 10 meters-long skin boat with wooden frame, is

usually rowed by women with short, broad-bladed oars; it can carry many

people and much goods and is mostly used when the family is moving to and

from the tent places, when they are catching capelins or are going caribou

hunting. Mostly due to the lack of big sealskins, the umiak has now nearly

disappeared in West Greenland, having been displaced by wooden boats.Skis are used by many Greenlanders in the winter; they were introduced

by the Danes, but the Greenlanders make them in a style of their own, covered

with sealskin.The old clothing had a birdskin shirt and coat, trousers and boots of

sealskin; in North Greenland caribou skin coats were used in the coldest

weather. The women wore short trousers and long boots, ornamented with skin

embroidery. They wore their hair in a knot or top. For kayak hunting the

men used coats of gutskin, lashed to the kayak hole, and tied around the face

and the wrists, so as to be entirely watertight.Nowadays the dress is much modified. The skin boots and skin trousers

are still in common use, and the women's boots and trousers have skin embroidery

in bright colors; with the large bead collar this is a handsome dress. More

and more people, however, especially in South Greenland, are now clad in

European fashion.The West Greenlanders are clever craftsmen and were especially so in

earlier times, when they had to make all their own implements. Their most

important tools were the long-handled whittling knife and the bow drill;

those of the women were the ulu — the woman's knife with a stem and a d c urved

016 | Vol_VIII-0093

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

blade, used for flensing, cutting the food, and parting the skins; also

the needle and various scrapers for skin preparation. The women are clever

seamstresses, especially skilled in making fine watertight boots. Now the

Greenlanders buy many of their tools in the shops.The old social culture of the West Greenlanders was very simple. There

was no real organization above the family, no clans, no tribes, no chiefs.

At each settlement there was usually an older, experienced man, who "thought"

for the settlement and whose advice was generally followed, although there

was no obligation to do so. In the family the father was the undisputable

head. Possession of land did not exist, but the house was regarded as the

possession of the family as long as it was inhabited. Other family possessions

were the umiak, tent, and different household utensils, while the kayak, hunt–

ing gear, dog sledge, dogs, tools, and clothing were possessed by individuals.

The killed game was not the property of the hunter alone, for he had to divide

it up according to certain rules among those who had taken part in the hunt,

and among other inhabitants of the settlement. Of the big game — walrus,

whale, bear — the hunter was allowed to keep for himself only a comparatively

small part of the animal. In time of famine everyone got some part of the

meat. When there was abundance, they could gorge enormous quantities of meat,

but they could also go without food for a long time if necessary. Hospitality

toward strangers was a matter of course. Altogether the old Greenland society

was one of mutual support, with no rich and no real poor.It was necessary for a hunter to have a wife. When a young man wished

to marry, he simply took the desired woman into his house, and she was then

expected to make some resistance, even if she did not wish to. Marriages

were often at an early age. Thus there were few unmarried people, mostly

017 | Vol_VIII-0094

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

widows whose men had perished in kayak hunting. Polygamy was not uncommon,

and wives were often changed after short periods. The position of the women was

quite good, especially if she had sons; but childless women were little

esteemed and were often divorced. Mothers suckled their children for long

periods, and children were brought up with no restraints. They were usually

named after another person, often a deceased relative; the name was regarded

as something independent of the person, which with the death of the person

could take its place in another living being. The dead were buried in a

stone cist accompanied by some of their implements.The religious beliefs of the West Greenlanders were rather vague,

and were influenced by the mighty and unintelligible nature around them.

Everything in nature had a soul; everything has its inua, which in a mystical

way was attached to the person or the thing. The human being has a w s oul,

which can be seen only by specially gifted people, the shamans or angakut .

In dreams it was though that the w s oul quits body and travels to distant

countries; it can be stolen by another, and if it is not restored by an

angakok, its owner will die. According to these beliefs, the soul d leaves

the body forever at death, but it exists, either in another person or in a

certain place where the souls live. Men dying in kayaks and women dying in

childbed go to a wonderful land below the earth with much sun and many seals.

Other souls go to a place high above the earth, where there are many berries

and many ravens. Here it is rather cold; they dwell in tents, and at night

they play ball with a walrus head, from which games comes the Northern Lights.Other important beings are tornat , the helping spirits of the shamans.

There they can call on for help if people are sick, or if the hunting is bad;

the most important is tornarsuk, the master of the souls of the dead. The

018 | Vol_VIII-0095

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

invocation of these spirts forms part of a seance during which shaman in

a trance is supposed to see supernatural things; the drum has an important

part in these seances.One of the most important spirts was the mother of the sea, Arnarquagseaq,

the mistress of the sea animals. She dwells at the bottom of the sea, and a

visit to her is one of the most difficult problems for the angakok ; but such

a visit is often necessary if one of the many taboo rules has been broken and

as a consequence the hunting has been bad. Sila, the weather, is another

mystical power, permeating everything. Other mystical sprits are tornit ,

the inland dwellers, and erqigtlit, the Indians; the tales about them are no

doubt allusions to ancient quarrels with other Eskimos and Indians on the

American mainland. The many tales of the Greenlanders are handed down ver–

bally from generation to generation.Most of the old spiritual culture of the West Greenlanders has now

vanished, even if some of the old tales still survive at remote places.

After the colonization, the missionaries worked hard to exterminate all the

old religious beliefs. The West Greenland population is now Christianized,

and nearly all can read and write; they are fond of going to church, even if

the Christianity they profess is often rather superficial; It is now the

intention to teach the whole population the Danish language. In Godthaab

is a high school, where young Greenlanders receive further education; the

cleverest students are sent to Denmark to continue their education. A

number ever of the higher officials are now of Greenland extraction.

019 | Vol_VIII-0096

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

The East Greenlanders

The East Greenlanders, numbering about 1,300, inhabit the east coast

of Greenland, most of them (about 1,100) in Angmagssalik District; in 1925

a group of Angmagssaliks was moved to Scoresby Sound, and in later years

another group settled at Skjoldungen on the stretch between Angmagssalik

and Cape Farewell.Graah, the first white man to penetrate the east coast north of Lindenow

Fjord, in 1829, did not reach Angmagssalik, but had much intercourse with the

Eskimos, numbering about 500, who then inhabited this coast. It was Gustav

Holm, who on his famous umiak expedition of 1884 first reached Angmagssalik

and wintered there. Owing to the works of Holm and Thalbitzer, the Angmag–

ssaliks are one of the best known Eskimo tribes. A trading post was first

established among them in 1894 and they came under Danish government. The

main settlement is now the colony Angmagssalik with about 100 inhabitants;

they also inhabit about 20 smaller settlements, of which only there are

permanent, with school, the others changing from year to year.The culture of the Angmagssalik Eskimos seems to have been derived from

that of the West Greenlanders, but from a rather old stage of it. From the

evidence of archaeology, the Angmagssalikers probably migrated from the

west coast in the 17th or 18th century. Since then they have lived a rather

isolated life, having had only a little communication with the West Greenlanders

at the "market place" at Aluk near Cape Farewell, where people from the two

coasts often met and exchanged goods. But this did not prevent a distinct

local cultural development in Angmagssalik.When Holm arrived at Angmagssalik, the annual hunting cycle was as

follows: In the spring basking seals were hunted on the ice; in June nearly

020 | Vol_VIII-0097

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

the whole population gathered for capelin fishing at a place in Angmagssalik

Fjord, and then they moved to the tenting places, hunting bladdernose and

fjord seals from kayaks. When the ice was formed seals were caught at the

breathing holes. Often this hunt was made by two men, one of them lying

down, looking for the seal through the hole, the other holding a long harpoon

with a fixed but movable head, thrusting it when the other man called out.

The kayak and its implements also differ in some respects from those of West

Greenland; the kayak here is broader, the float consists of two small sealskins,

and the lance is thrown without a throwing board.The large common house, used in West Greenland in the 18th century, is

still in use in Angmagssalik; usually there is a small entry instead of a

passageway, and the windows have glass panes. In recent years more and more

of the younger hunters are building smaller houses of West Greenland type.The old household utensils were lamp and cooking pot of soapstone, water

pails and urine bowls of good coopery work, blubber and meat trays of wood.

Fire was made by drilling in wood, for driftwood is rather abundant on this

coast. Most of the old utensils are still in use, but are more and more

disappearing as the use of purchased manufactured articles increases.The umiak is still used. The dog sledge is small, fitted for traveling

over mountainous land, as the sea ice is often unsuited for sledge travel.The clothing is of sealskin. In the house men and women formerly went

almost naked, wearing only a small triangular piece of skin, called a n a â tit ,

between the legs. Out of doors the women wore visors, short trousers and

long boots. When kayak hunting the men wore caps with visors in European

fashion, made of foxskin or embroidered sealskin; they also wore a hair-band,

and crosswise on chest and back they had a sealskin thong carrying amulets.

021 | Vol_VIII-0098

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

Women wore their hair in a big knot on top of the head. The women were

very clever at skin embroidery, made of dark and light skins in different

patterns.The most conspicuous thing about Angmagssalik implements is their

ornamentation. Small figures of bone and ivory are nailed on many wooden

object; throwing boards, water sails, meat trays, tool boxes, and the

beautiful eye-shades; the figures depicted are mostly seals, but there are

also whales, men, kayaks, or geometrical figures. Figures of men, animals,

and spirits are carved out of wood, often with great skill. Also maps are

sometimes cut out in wood.The drum was of great importance; it was used not only as accompaniment

when they sang their old songs, but also in the drum dance, their way of

settling quarrels: two men (or women) take turns in singing lampoons about

each other to the accompaniment of the drum, while the whole population of

the settlement listens; the idea is to get the listeners to laugh and in this

way cast scorn upon the opponents. Such a drum fight can l a st for weeks,

until one of the contestants becomes tired and gives up, an effective and

bloodless way of settling disputes. Earlier, murder and violence were very

common, and blood vengeance feuds were often carried on from generation to

generation.The religious beliefs of the Angmagssalik people are in the main the

same as the West Greenlanders', with local variations.Altogether the Angmagssalikers live in a more old-fashioned way than

the West Greenlanders, and here are still often found old cultural elements

which elsewhere have disappeared. There have been no such economic changes as have

occurred in later years in West Greenland. There has been, however, a certain

022 | Vol_VIII-0099

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

influence from the West Greenlanders, who dwell in Angmagssalik as priests,

teachers, craftsmen, etc. This can be seen in house building, clothing,

and in many other ways. All the Angmagssalikers are now Christianized,

but the old people still remember much of their old beliefs and their old

tales. Seal hunting remains the principal occupation, and we can still see

in Angmagssalik a good deal of the old Greenland life among a nearly pure

Eskimo population.

023 | Vol_VIII-0100

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Birket-Smith, Kaj. "The Greenlanders of the Present Day." In

Greenland , Vol.II, Copenhagen, 1928.2. ----. "Ethnography of the Egedesminde District." Medd. Om Grønland ,

vol. 66, 1924.3. Cranz, D. Historie von Grönland, I-III, Barby, 1770.

4. Egede, Hans. Det gamle Gronlands nye Perlustration eller Naturel–

Historie , Copenhagen, 1741.5. Fabricius, O. "Nøiagtig Beskrivelse av alle Grønlendernes Fange–

Redskaber ved Selhunde-Fangsten." Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes

Saskab Skrivter , [ ?] Vol. V. 1818.6. ----. "Nøiagtig Beskrivelse over Grønlendernes Landdyr-, Fugle- og

Fiske-Fangst med dertil hørende Redskaber." Kgl.D.Vid.Selsk.

Skr., Vol.VI, 1818.7. Hansen, Søren. "Bidrag til Vestgrønlendernes Anthropologi," M.O.G.

Vol. VII, 1893.8. Holm, Gustav. "Ethnologisk Skizze af Angmagssalikerne." M.O.G. vol.10,

1887.9. Holtved, Erik. Polareskimoer , Copenhagen, 1942.

10. Kroeber, A.L. "The Eskimo of Smith Sound." Bull . American Mus.Nat.Hist.,

Vol.12, 1900.11. Mathiassen, Therkel. "Prehistory of the Angmagssalik Eskimos." M.O.G.,

Vol.92, Pt. 2, 1933.12. Mikkelsen, Ejnar. De østgrønlandske Eskimoers Historie, Copenhagen, 1934.

13. Mylius-Erichsen, L., and Moltke, Earald. Grønland, Copenhagen, 1906.

14. Mansen, Fridtjof. Eskimoliv , Kristiania, 1891.

15. Porsild, M.P. "Studies of the Material Culture of the Eskimo in West

Greenland," M.O.G., vol.51, 1915.16. Rasmussen, Kund. Nye Mennesker. Copenhagen, 1905.

17. ----. Grønland langs Polhavet , Copenhagen, 1919.

18. ----. Myter og Sagn fra Gronland , Vols. I-III, Copenhagen, 1921-25.

19. Rink, H. Eskimoiske Eventyr og Sagn , Vols. I-II, Copenhagen, 1866-71.

024 | Vol_VIII-0101

EA-Anthrop. Mathiassen: Greenland Eskimos

20. Steensby, H.P. "An Anthropogeographical Study of the Origin of the

Eskimo Culture," M.O.C. , vol.53, 1916.21. ----. "Contribution to the Ethnology and Anthropogeography of the

Polar Eskimos," M.O.G., vol. 34, 1910.22. ----. "Ethnografiske og antropogeografiske Rejsestudier i Nord–

grønland," M.O.G., vol.50, 1909.23. Thalbitzer, W. "The Ammassalik Eskimo," M.O.G., vols. 39-40, 1914 and 1923.

24. ----. Grønlandske Sagn om Eskimoernes Fortid , Stockholm, 1913.

Eskimoernes kultiske Guddomme. Studier fra Sprog og Oldtidafor–

skning , Copenhagen, 1926.Therkel Mathiassen