-

The Copper Eskimos

Encyclopedia Arctica 8: Anthropology and Archeology

The Copper Eskimos

001 | Vol_VIII-0048

EA-Anthropology

[Diamond Jenness]

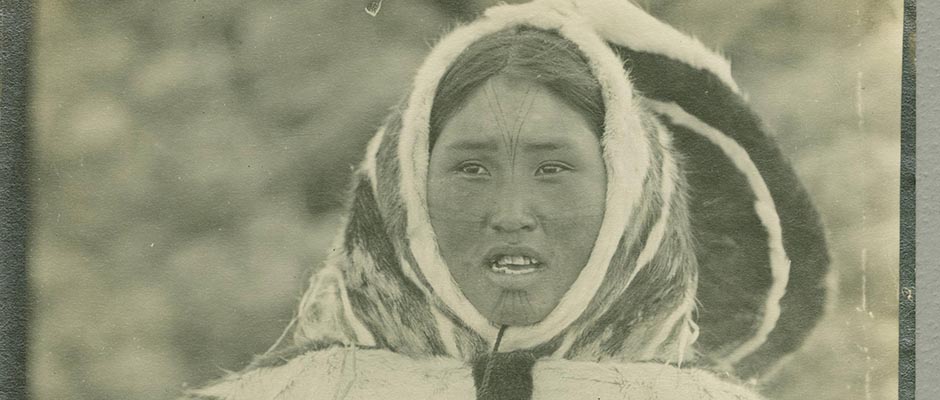

THE COPPER ESKIMOS

In historical times the Copper Eskimos occupied the mainland coast of Arctic

Canada between approximately longitudes 102° w. and 118° W., as well as the

southern and western coasts of the adjacent Victoria Island and the southern

end of Banks Island. Like the Indians immediately south of them, they re–

ceived the appelation "Copper" because in many of their tools and weapons they

substituted the natural copper they picked up on the surface of the ground for

the stone that other Eskimos were using prior to the introduction of iron by

Europeans. Another name, "Blond" Eskimos, given to them occasionally in former

years, is now generally discarded. It arose from the belief of Vilhjalmur

Stefansson that a certain percentage of them had lighter eyes and hair, and

features more European-like, than the Eskimos he had encountered in the Mac–

kenzie River Delta and in Alaska, traits which suggested to him the possi–

bility of early Scandinavian (Viking) admisture. This theory, however, has

not as yet been substantiated, and Stefansson himself in his writings has pre–

ferred the more usual term "Copper Eskimos."Samuel Hearne was the first European to come in contact with this arctic

group. In 1771 he journeyed with a party of Chipewyan Indians from Churchill

002 | Vol_VIII-0049

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

to the mouth of the Coppermine River, where his companions ruthlessly mas–

sacred a small band of Copper Eskimos near a place now known as Bloody Fall.

The next white man to fall in with them was Captain (afterwards Sir John)

Franklin when he surveyed the southern shore of Coronation Gulf in 1821. After

Franklin's day they were visited by several explorers, and even by two or three

traders, but no one attempted to make a detailed study of their customs until

Stefansson traveled through the western portion of their territory in 1910 and

1911. Part of a Canadian expedition which he led to the Arctic again in 1913

then wintered for two years in Dolphin and Union Strait, and in Volumes XII

to XVI of the reports of that expedition its ethnologist, Jenness, greatly ampli–

fied Stefansson's earlier description. Finally, Knud Rasmussen, leader of the

Danish Fifth Thule Expedition to the west coast of Hudson Bay in 1921-24,

lingered among the eastern Copper Eskimos during his long sled journey [ ?]

across arctic America to Alaska, and he, too, has given us a most illuminat–

ing account of their religion and folklore.The Copper Eskimos were not a very numerous group. Jenness estimated their

number at between 700 and 800, scattered in groups of from 20 to 100 in dif–

ferent districts. The census of 1941, just 25 years later, made it 682. Whether

it ever exceeded this figure, which gives a ratio of about 1 person to every

4 miles of coast line, is unknown. Certain bands had traditions of depopula–

tion, and remains of Copper Eskimo habitations have been found beyond the limits

of their a wanderings in recent times; but these clues are too faint to warrant

any conclusion.To Stefansson and Jenness coming from the west, and, though to a lesser

extent, to Rasmussen coming from Greenland and Hudson Bay, there were many

peculiarities of life among the Copper Eskimos, in addition to their use of

003 | Vol_VIII-0050

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

copper, that set them off from Eskimos elsewhere. Thus they lacked the large

open traveling boat or umiak , and they never used the smaller one-man kayak for

hunting seals. Harpoon heads, fishhooks, knives, and other tools and weapons

had unfamiliar shapes, pottery was unknown, and the soapstone cooking pots and

lamps were unlike those made in other regions. The clothing, which, as usual,

was tailored principally from caribou fur, followed a local style nearer,

perhaps, to Hudson Bay styles than to Alaskan; and the only winter dwellings

were the quickly perishable snowhouses. The latter were often grouped together

in unusual patterns, never had cooking porches, and were never lined with skins

as in parts of Hudson Bay.Environment could conceivably explains a few of these peculiariaties.

The waters around Coronation Gulf are too sheltered to harbor the whales, wal–

ruses, and belugas that are fairly abundant from the Mackenzie Delta westward,

and again in Hudson Bay; hence, one would not [ ?] expect the Copper Eskimos

to possess the special appliances, or to practice the special rites, associated

with the hunting [ ?] of those sea mammals in other regions. Again, they could

hardly build permanent houses of whale bones and sod, such as were common in

the Hudson Bay region, since there were virtually no whales; nor could they

build log cabins like those prevalent in the Mackenzie Delta and Alaska, because

there are no trees along the arctic coast and only a negligible quantity of

driftwood ever reached their shores. Environment, however, does not explain

why they never hunted seals from kayaks during the summer months, nor why they

failed to build houses of stone. There are some ruined stone houses in their

territory, it is true, but archaeology has shown that these were left by an

earlier people.

004 | Vol_VIII-0051

EA-Anthrop. Jeness: Copper Eskimos

The most noticeable of their peculiarities, their replacing of stone by

copper, was conditioned, of course, by the occurrence of float copper near the

banks of the Coppermine River. It is interesting to observe that the Copper

Eskimos of the 20th century never used stone for knife blades, or for spear and

arrow points, nor did they recollect they forefathers had ever done so;

yet Hearne noticed that half the arrow points of the Bloody Fall natives were

of stone. It would seem, therefore, that the metal grew in popularity during

the last two centuries. [ ?] The copper Eskimos can hardly have discovered for

themselves that it could serve as a malleable stone, for their predecessors in

southwest Victoria Island, a Thule-culture Eskimo group who apparently arrived

there from the west, had used copper in one or two implements; and near Iglulik,

in the north of Hudson Bay, Rowley discovered some fragments of copper in remains

of the Dorset Eskimo culture that must date back eight or more centuries. Even

these earlier Eskimos were probably not its discoverers, for the Indians of the

Mackenzie River Basin have been familiar with copper for several centuries, and

those around Lake Michigan were mining it during the first millenium A.D.It was the environment that limited the food resources of the region.

Seals were not particularly plentiful, caribou and fish were seasonal and also

not over-abundant, musk oxen scarce, and edible roots and berries almost non–

existent. Life was an unbroken round of sealing on the frozen sea ice during

the winter and spring months, fishing in late spring and again in the fall,

and caribou hunting during the brief summer. In some districts every fifth winter

or so was a time of scarcity, every fifteen th winter of famine.The limited food supply made the communities or bands small and unstable.

Twenty or thirty families might build their snow huts side by side during the

winter, but they dispersed during the spring and early summer to roam the land

005 | Vol_VIII-0052

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

as single units, or in tiny groups of two or three families together, and the

composition of the next winter's community in that locality was generally rather

different. Many communities in the western Arctic, and also in the eastern, were

both larger and more enduring than any which existed among the Copper Eskimos,

simply because the food resources were more abundant.The lack of any organization in these communities was characteristically

Eskimo. There were no chiefs, no persons in authority. Individuals owned the

things they could make for themselves, e.g., knives, cooking vessels, etc.; but

the land was common property, and the food it yielded was shared by all alike.

There were no ceremonies at funerals, and none at marriage. The latter took place

at an early age, but the union was quite unstable until a child was born,

when it generally lasted for life. Polygamy was uncommon, partly because males

preponderated over females in the population, partly because it was not easty

for a hunter to support more than one wife; and polyandry was discouraged because

it invariably led to quarrels and murder, thereby instigating new blood feuds. A

subdued tone of uneasiness pervaded every community because of these constantly

recurring blood feuds, which, here as elsewhere, constituted the foulest blot on

Eskimo social life. In conjunction with the practice of infanticide, especially

of girl babies, and the hazards of life generally, it effectively counterbalanced

a fairly high birth rate, the fecundity of the Copper Eskimos being no less,

apparently, than that of other races.We remarked earlier that the Copper Eskimos lacked the beliefs and prac–

tices associated with whaling that were current among the natives in both the

eastern and western Arctic. Like all Eskimos, nevertheless, they denizened the

universe with a multitude of spirits that were presumed to control the phenomena

of nature and the abundance of game. Rasmussen thought that a few philosophers

among them had attained to the conception of a supreme deity; but this is by no

006 | Vol_VIII-0053

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

means certain, since they may have derived the idea from missionaries and

their converts who were active in the area for several years before Rasmussen's

visit. They did, however, recognize a sky god, though they thought him too

remote to interfere very actively in human affairs; and they possessed the

Sedna myth of the eastern Arctic, the belief in a female deity at the bottom

of the sea who regulated the supply of seals. Perhaps the most solemn ceremony

in their [ ?] lives was their formal intoning of prayers to this deity during

periods of winter famine. Any native, man or woman, might obtain a personal

spirit helper and set up in practice as a shaman, but his influence and prestige

depended entirely on his charater and his powers of leadership. Numerous

taboos were prevalent, as one would expect in a primitive people. Some were

permanent and handed down from generation to generation, others temporary,

imposed by the shamans for a period only; but the personal taboos that were

so marked a feature of life in the Mackenzie Delta and in northern Alaska were

conspicuously absent. Closely associated with the taboos was a ritual dis–

tinction, made also by the Hudson Bay natives though not by the western ones,

between products that were derived from the sea and those that came from the land.The Alaskan natives often consumed one or two whole evenings in narrating

a single folk tale; but the Copper S E skimos, who were less addicted to this

form of entertainment, commonly clipped their tales, giving only the high

lights and leaving most of the details to the imaginations of their listeners.

In this respect, as well as in the contents of their tales, they resembled

more closely the natives of Hudson Bay. Their dancing, too, the music of their

songs, and the large tambourines that accomp a nied their singing and dancing,

were eastern in style rather than western; and they indulged in the song contests

that evoked such bitter rivalry in Greenland, but were unknown in the western

007 | Vol_VIII-0054

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

Arctic. Art, if we exclude the ornamentation of fur clothing, was little

developed as compared with other regions; but this may not have been due to lack

of talent, for one could find a few simple figures of fish and birds that were

quite neatly carved in bone.The dialect spoken by the Copper Eskimos was, on the whole, intermediate

between those of north Alaska and of Hudson Bay. It had the eastern tendency to

nasalization, and to the substitution of the softer voiced consonants for the

harder voiceless ones; but it lacked some of the eastern sound changes — e.g.,

rn in place of nr ; and it retained the western too conjugation endings in many

verbs.From the description given above it is evident that the Copper Eskimos

were somewhat nearer akin to the natives of the eastern Arctic than to those

of the western. Their own traditions were silent about their origin. They

knew that they were not the first inhabitants of the area around Coronation

Gulf, for here and there were traces of an earlier people, a people who had

lived in stone houses, or in houses made of wood and sods, of which the ruins

were visible in several places. Unlike the Copper Eskimos, these people

occasionally hunted the whale in open skin boats, made many cooking vessels

of pottery [ ?] in place of stone, and used so little copper in their tools and

weapons that they could almost be said to have been ignorant of that metal.

Jenness has shown that they were probably estern Eskimos, and has suggested

that they may have retreated to the west again when the narriw waters of Coro–

nation Gulf proved unsuitable for whales. He thinks the Copper Eskimos who

displaced [ ?] or succeeded them came from the south, where they constituted the

008 | Vol_VIII-0055

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

outermost wing of a horde of inland Eskimos who, 500 to 600 years ago, streamed

out of the barren lands east of Great Bear and Great Slave Lakes and took

possession of the littoral of Hudson Bay, a few of them even reaching Greenland.

This theory of their origin is now widely accepted, because it accounts more

readily than any other for their lack of umiaks, their ignorance of the hunt–

ing of seals from kayaks, and their rather close resemblance to the present–

day Eskimos of Hudson Bay.In the days of Stefansson and Jenness the Copper Eskimos still wore the

same style of clothing as their forefathers, and used the same tools and weapons.

The quarter ce n tury that has elapsed since that time has brought many changes.

Bows and arrows have disappeared, for every man now owns a high-powered [ ?]

rifle. Iron and steel are so plentiful that copper has gone entirely out of

use. The snow but still holds its own, but there are many frame houses also,

while the cloth tent has largely displaced for summer use the former tent of

seal or caribou skin. The old caribou-fur clothing is still much preferred

for winter wear, but it has taken on a western [ ?] cut that is much less pic–

turesque than the original, and in summer practically all the natives now wear

garments of wool and cotton. Kayaks, always scarce, have vanished completely,

but there are numerous canoes and even a few motorboats. Nearly all Copper

Eskimo families now possess sewing machines, and many have radios and gramo–

phones also.Nor is it only the material culture that has changed. The whole manner

of life has been revolutionized since 1916, when the Hudson's Bay Company estab–

lished the first permanent trading post in their midst and diverted their

energies to the trapping of foxes and other fur-bearing animals. For trapping

009 | Vol_VIII-0056

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

is profitable only on land, and then only during the winter months when the

furs of animals are in their prime. The Eskimos had therefore to modify the

yearly cycle of their lives. Whereas in earlier times they used to spend the

months from April to November on the land, hunting caribou and fishing for

trout and salmon, then in winter erect their snow huts on the sea ice and

hunt seals, today they shorten their stay on the sea ice in order to trap

foxes along the shore, and some of them have given up sealing altogether,

except during the summer season of open water [ ?] when they can shoot the animals

from canoes. Furthermore, since foxes cannot replace seals for meat and oil,

the Copper Eskimos, like their kinsmen elsewhere, are now consuming consider–

able quantities of imported foods, particularly flour, sugar, and tea; and

for cooking their meals they frequently use primus lamps that burn coal oil

instead of the old saucer-shaped lamps that burned seal blubber. Since the

construction of a small airplane landing field at the mouth of the Coppermine

River, more than one sophisticated native has gazed on his ancestral hunting

grounds from the level of the clouds.Hand in hand with these economic changes have gone a few changes in the

social life. Intervention by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police has effectively

discouraged murder (including infanticide) and the practice of the blood feud,

thus increasing the security of life. The Copper Eskimos no longer fear to

travel far afield, to visit distant places like the Mackenzie River Delta, or

to associate with the once dreaded Indians of Great Bear Lake. The family —

the man, his wife, and their children — has remained the fundamental unit of

society, for such a unit does not readily change; but the old grouping into

bands, each bearing a definite name and restricting itself to a definite district,

010 | Vol_VIII-0057

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

has gone out of existence now that every man feels free to hunt and set up

his fox traps wherever he wishes, provided he does not encroach too closely

on his neighbor's trap line. The compact winter villages of the bands, with

their contiguous snow huts from which the hunters and their dogs marched out

each morning to hunt seals, have been largely replaced by the single dwellings

of trappers — some of them log cab i ns — spaced at intervals along the coast.

The Copper Eskimo is becoming more individualistic now that he is confronted

with new ideas of property that are not easily reconciled with his former

communistic practices. Even the simple amenities of life have changed.

Western Eskimos and half-breeds have brought in new pastimes and new dance

forms, and the church services of the missionaries have replaced — publicly

at least — the seances of the shamans. Many of the old religious beliefs

and taboos still survive no doubt, but they have been largely submerged be–

neath the newly accepted Christianity.In one respe c t, contact with the outside world has brought unqualified

calamity. Prior to the 20th century the Copper Eskimos appear to havebeen

free from all but two diseases, simple colds that attacked them when they

moved from their drafty summer tents into the rather stuffy snow huts, and

some internal malady that has [ ?] never been diagnosed, but may have been

appendicitis. In 1926 influenza was introduced amongst them and carried off,

according to one estimate, nearly 20% of the population. About the same

time white traders were responsible for the appearance of a few cases of

syphilis and gonorrhoea; fortunately[?], they did not persist. Tuberculosis,

however, did take root, and in 1930-31 attained such virulence that of the

100 or so natives who were then wintering around the mouth of the Coppermine

River no less than 20 died within 8 months.

011 | Vol_VIII-0058

EA-Anthrop. Jenness: Copper Eskimos

Tragic has been the history of the family with which Jenness wandered

around southwestern Victoria Island in the summer of 1915. His adopted mother

Icehouse was a victim of the influenza epidemic of 1926. Ikpuck, his father,

was suffering from tuberculosis in 1930, but was able to remain active up to

his disappearance during a hunting trip two years later. Of Icehouse's two

children the elder, a male, was reported to be in good health as late as

1940; but the younger, Jennie, wasted away with tuberculosis in 1931, at

the age of about 27, after two of her three children had perished from the

same disease and her husband had contracted it also. Jennie knew that her days

were numbered, and only three months before herd death she radioed a message

to her "brother" Jenness from the wireless station that had just been erected

at Coppermine. Translated the message read" It would make me very happy if

you would visit us next summer when the warm weather arrives. I will make

you a fur coat if you come. But I may not live until then. I do not know."Diamond Jenness